Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD: What are the key risk factors for DR development and progression?

Caroline R. Baumal, MD: There are a number of known risk factors for DR progression, although our ability to definitively predict which patients will progress is still limited. The classic risk factors associated with risk of progression are the duration of diabetes, type 1 versus type 2 diabetes, and age of onset.6 In addition, the individual’s level of exercise, cholesterol, cardiac health, blood pressure, diet, and smoking history impact progression of systemic disease,7 thereby conferring risk for ocular sequelae. Similarly, the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level is a marker for how well blood glucose levels are controlled, and this is something that is easy to discuss with patients.8

Joseph M. Coney, MD: To me the most important thing is the severity of DR at the time of presentation. In the ETDRS patients with moderately severe to severe NPDR were at greatest risk of progression to PDR. At 1 year, 26% and 51% of patients, respectively, progressed to PDR from baseline.9 Therefore, I tend to be more aggressive and usually recommend treatment sooner for those patients at higher risk.

Allen Chiang, MD: In addition to clinical factors, socioeconomic factors are important to consider because they impact health outcomes. There are increased barriers to care among individuals in lower socioeconomic strata and of certain ethnicities, ranging from being underinsured to not having insurance at all. A lack of education about diabetes and its ocular complications is also common. Identifying these patients as higher risk demands careful thought and intention as far as patient education and the treatment approach.

Szilárd Kiss, MD: I have gained a slightly different perspective on socioeconomic risk factors. I practice at an academic center on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City, and we have a relatively affluent and insured patient population. However, we have found that fewer than 20% of our patients with diabetes receive annual eye examinations, despite having adequate insurance and despite the fact that we offer same-day appointments, which are thought to remove an important barrier. To counteract that, we have placed Optos wide-field cameras in the primary care physicians’ offices in our network to try and capture some of those patients. We have concluded that the most significant factor for our patients in terms of not receiving their annual exams is just that life gets in the way—patients with diabetes are typically of working age and may have work, family, and other obligations, and so they may not be as attentive to their medical needs as we would hope. On top of that, a patient with early ocular changes from diabetes is most likely going to be asymptomatic, and so they may not perceive a need for regular screening.

Dr. Wykoff: Are there ways we can improve in terms of communicating the importance of eye care to this population?

Dr. Coney: Ancillary tests, such as wide-field FA and OCT, are great visual tools that I implement in my practice to increase awareness and compliance. Reviewing the retinal pathology, such as microaneurysms, abnormal blood vessels, bleeding, swelling, and large areas of non-profusion, informs patients that they have a sight threatening condition. I reinforce the importance of early detection and treatment, and that “no one needs to go blind if we catch it early.”

Dr. Kiss: The HbA1c level was mentioned previously, and while that is a critically important risk factor for DR development and progression, patients sometimes disengage from the conversation when we begin discussing that with them. On the other hand, showing an image can be powerful. At least in my experience, patients with diabetes understand that something is wrong, but they do not want a lecture, so showing them the damage might be a better way to get their attention. It does not have to be extensive. You can point to the damage and say, “We do not want the disease to reach the center.” I have also found that getting the family members involved can be beneficial, as well.

Case 1: Surgery Versus Laser Versus Anti-VEGF

By Caroline R. Baumal, MD

Initial Evaluation:

- A 38-year-old white woman with insulin-dependent diabetes referred for surgical consultation for a tractional retinal detachment.

- VA is 20/20 OU. Vitreous hemorrhage is OS.

- She previously received panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in both eyes.

Imaging:

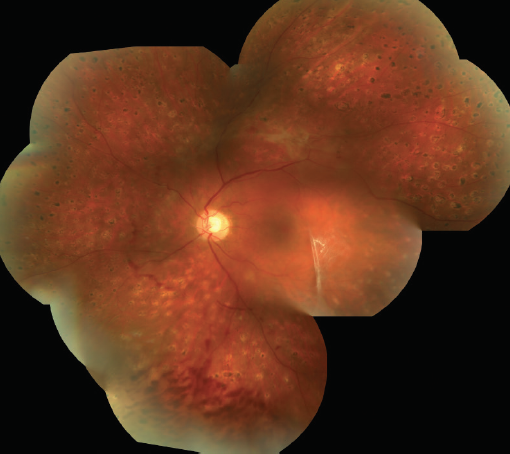

- Imaging of the left eye showed traction temporal to the fovea but not involving the fovea (Figure 1).

- OCT angiography (OCT-A) (3 mm) of left eye showed peripheral nonperfusion, cystic changes, and neovascularization.

- Various imaging in the right eye showed previous PRP, no diabetic macular edema (DME), but indication of active proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Image of left eye.

Figure 2. OCT-A of right eye.

Discussion

Caroline R. Baumal, MD: This patient has active PDR in each eye but no DME. Aside from an occasional floater, the patient reports no other symptoms. She came to me for a consultation because her referring doctor told her she needed a vitrectomy. I did not believe there was a need for surgery and instead injected anti-VEGF agents into each eye. My thinking was that additional laser would not address the neovascularization. Would anyone go to surgery with this patient or would anyone consider laser? What about anti-VEGF therapy?

Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD: The left eye appears to be symptomatic with active vitreous hemorrhage. However, the right eye is less concerning. Why did you pursue treatment in that eye?

Dr. Baumal: I treated based on the FA showing neovascularization and leakage. I often treat in this situation and follow the patient with OCT-A.

Dr. Wykoff: With good PRP, you may have stability of neovascularization with leakage that is not going to go away. I do not think our goal is to eliminate all leakage. It is to create stability in a functioning eye.

Joseph M. Coney, MD: I agree. Not all neovascularization needs to be treated, but in this case, additional PRP would have been of benefit for the vitreous hemorrhage in the left eye. Looking over the imaging, it looks like the previous PRP in the right eye was incomplete, and there may be a need to add more laser.

Szilárd Kiss, MD: I would not have treated either eye until I saw change in status of the neovascularization based on the fact that this patient was asymptomatic at the time of the examination. Neovascularization can remain stable in many cases.

Dr. Baumal: Unfortunately, the DR was not stable in this patient. After a series of injections in each eye, the patient developed a vitreous hemorrhage in the left eye, likely secondary to the tractional retinal detachment. At that time, we performed vitrectomy and continued to use anti-VEGF injections on a prn basis. The surgery went well, and I am inclined to believe that using anti-VEGF agents is a prime reason why.

Dr. Baumal: Utilizing imaging is an excellent way to show established DR to individuals. In addition, I continue to use the HbA1c because it is easy to comprehend, and patients are often aware of this parameter from the primary care physician.

- The message can be fairly straightforward and is also supported by the American Diabetic Association, which recommends targeting HbA1c below 7.0 % to reduce development and progression of DR.10-12

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial also revealed a strong exponential relationship between HgbA1c and DR progression. For every 10% decrease in HgbA1c (for example, 10% to 9%), there was a 43% to 45% decrease in the risk of progression of DR.

- Glycemic control is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for DR.13

In fairness, the HbA1c level is not the only or strongest predictor of progression, but it can still be a useful surrogate for how well the systemic diabetes is controlled, and ultimately, that is what I want to advocate for. Even if the correlation between controlling HbA1c and avoiding progression is not perfect, the underlying principal is that we are trying to guide patients to take some control of their situation.