Protocol S

Dr. Wykoff: That is a good point, and it segues into how we can use clinical trial data to guide real-world practice patterns. Protocol S is the only prospective trial that uniformly randomized treatment-naïve patients with PDR to anti-VEGF or PRP.3,4 The specifics of the treatment protocols in this trial are worth discussing.

- In the PRP arm, patients received PRP, and if the neovascularization worsened, the patient received additional PRP.

- In the anti-VEGF arm, patients received six monthly loading doses, but the last two could be deferred if the neovascularization resolved.

- After 6 months, if the neovascularization improved or worsened, the patient was treated, and if the neovascularization was stable or resolved, the patient was not treated. In other words, after 6-months the retreatment protocol was as needed.

How does that compare to what you are doing with respect to loading doses and subsequent injections?

Dr. Chiang: I treat monthly until I see regression, which I have often observed after two to three treatments. At that point I start to extend. In my experience, patients receiving only anti-VEGF injections are getting five to six injections in the first year, which is about what we saw in Protocol S. For patients who I sense are at higher risk for noncompliance, perhaps because of other systemic or social issues that may be likely to prevent them from following up, I will discuss and initiate laser pretty early in the course of treatment.

Dr. Kiss: Six monthly injections are a burden for many patients, and some do not even require six injections before there is resolution. I perform three injections and repeat the FA, and if there is still neovascularization, I continue injections. I prefer to go to surgery with noncompliant patients, especially if there is any element of traction present. My thinking is that removing the vitreous, perhaps placing some light far peripheral laser, and performing a posterior hyaloid detachment will prevent tractional detachment from occurring.

It is like a prn protocol. If we remember back to the ETDRS study, 40% of patients had recurrence/presence of neovascularization even after laser,9 and there are not good data to say that repeating laser will be effective and may lead to loss of vision on it own. So, I treat based on the presence of abnormal vessels.

Dr. Coney: I do not have a set protocol, per se, except to say that I try to tailor the approach to the individual patient and what is going in the eye. PDR is a basket term, and there are patients at higher and lower risk for progression, even within this group of patients. Generally speaking, though, the first 6 months of treatment are really crucial, so I tell patients that we are going to plan on six monthly injections and repeat the FA after the fourth injection. About a third of patients have regression in the first 3 months, and it has been our experience that there is typically significant improvement between the fourth and sixth injection. Ideally, I will be able to observe them after six injections to see how they respond, as long as there is no progression of the DR. But this approach also gives patients an endpoint, at least an interim one, which is important for many of my patients. I see many people at my clinic who travel significant distances, and travel can be difficult during winter months, so I tend to over treat in the fall months to make sure they are covered. That said, using anti-VEGF injections is not a guarantee there will be regression of the DR, so there is still a role for laser especially for noncompliant patients.

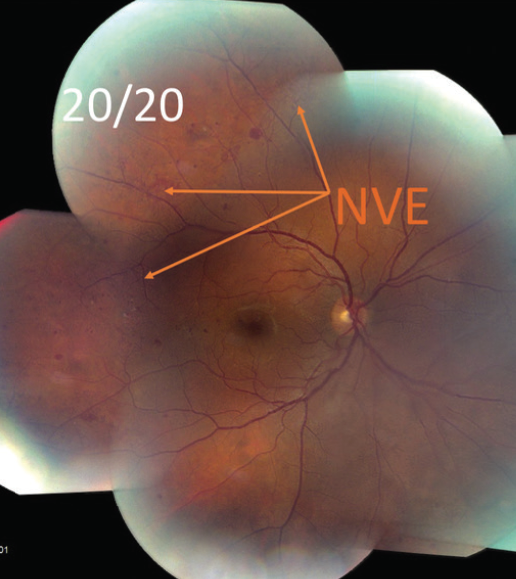

Case 5: Peripheral Neovascularization in an Eye With Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

By Allen Chiang, MD

Case Overview:

- A 29-year-old male physician with type 1 diabetes mellitus for 15 years.

- VA is 20/20 OU.

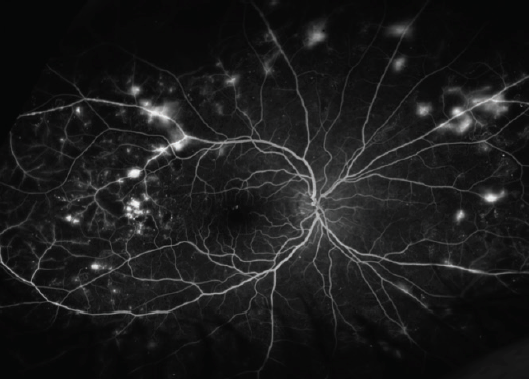

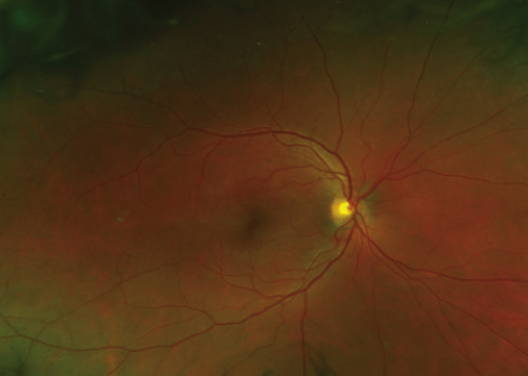

- Fundus photography showed possible neovascularization (Figure 1A) that is confirmed on fluorescein angiography (FA; Figure 1B).

- Diagnosis: proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) in each eye without diabetic macular edema (DME); trace vitreous hemorrhage in the right eye. Despite mild visual symptoms, patient states a preference for initiating therapy to address the underlying disease process.

Figure 1A. Fundus photography showed possible neovascularization elsewhere (NVE).

Figure 1B. FA confirmed neovascularization elsewhere (NVE).

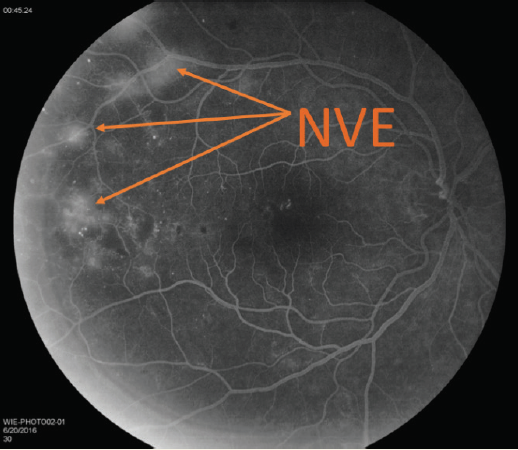

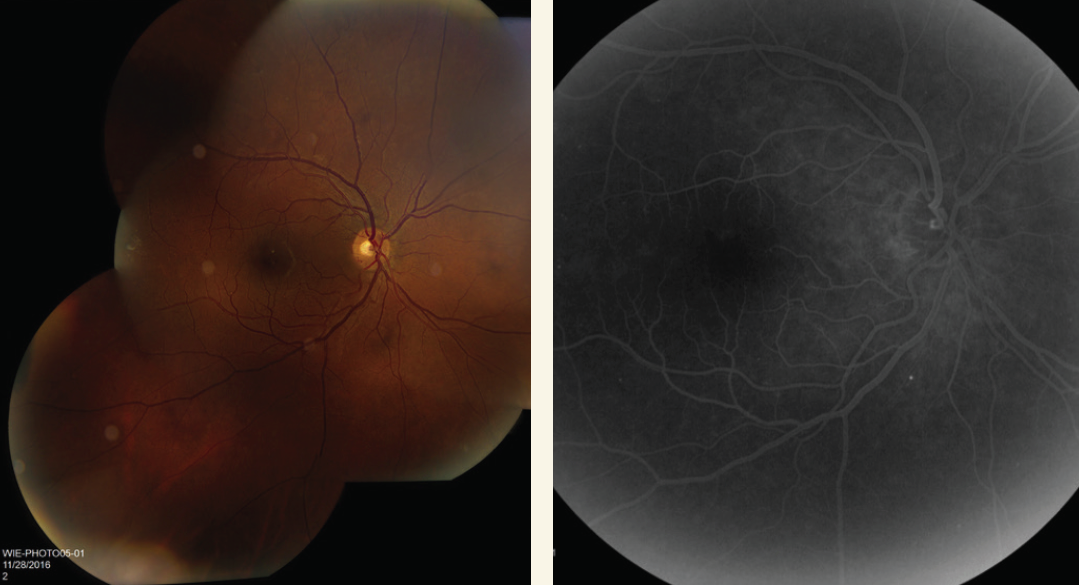

Treatment Overview:

- After three monthly injections of bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech) neovascularization had regressed (Figure 2).

- The patient did not continue with recommended follow-up appointments and returned about 5 months later with diffuse neovascularization that was more evident on FA (Figure 3A) versus fundus photography (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Neovascularization has regressed following three monthly injections of bevacizumab.

Figure 3A. FA 5 months later.

Figure 3B. Fundus photograph 5 months later.

Allen Chiang, MD: How would you proceed with treatment at this point?

Szilárd Kiss, MD: I would offer surgery as an option for this patient. The patient has almost exclusively peripheral disease, which is associated with a remarkably high risk of developing vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy.1 My conversation with the patient would cover two points: the need for diligent follow-up and that we need to be as aggressive as possible. Our field is a little biased against surgery at this point, but my sense is that much of the surgical literature relates to 20-gauge surgery. With smaller-gauge surgery, either 25- or 27-gauge, we would be able to remove the posterior hyaloid and avoid severe consequences like tractional retinal detachment—especially if there is anti-VEGF on board. If I am already doing surgery on an eye like this, peripheral laser is a consideration. The long-term prognosis with surgery is fairly favorable.

Joseph M. Coney, MD: I would favor a combination approach, with anti-VEGF therapy supplemented by some light laser in the periphery. Wide-field angiography would certainly be helpful in determining the treatment approach.

Charles C. Wykoff, MD, PhD: Surgery is an option, but I would prefer to use anti-VEGF therapy. I would have a frank discussion with the patient to let him know that if he does not comply with the follow-up, there is significant risk of vision loss. I would want to use fixed monthly intervals, at least initially, and perhaps moving to 2-month intervals after that. Also, I like the idea of combination therapy with laser in the periphery.

Dr. Chiang: Compliance is a real concern because a lapse in follow-up can result in severe vision loss. This case illustrates that compliance can be a concern for even the highly educated patient due to more demanding life and job commitments. Fortunately, this patient did return. We moved to a treat-and-extend protocol with anti-VEGF injections followed by slightly more anterior panretinal laser.

1. Silva PS, Cavallerano JD, Haddad NM, et al. Peripheral lesions identified on ultrawide field imaging predict increased risk of diabetic retinopathy progression over 4 years. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(5):949-956.

Dr. Baumal: I look at the amount of neovascularization to guide whether to inject or apply laser. I usually give an anti-VEGF injection every 4 to 6 weeks until the neovascularization has improved, and after that I start to extend the interval. I will stop the injections if the neovascularization resolves completely and observe closely. By that point and time I will know if the patient is compliant with follow-up, and I can decide on using laser accordingly.

Dr. Wykoff: In my practice, I want to extend the interval between treatments as soon as I can. Dr. Coney alluded to the fact that among PDR patients, there are different categories of risk for progression. For those at lower risk of progression, I give one injection, and if there is improvement at the next visit 1 month later, I will inject again and extend to 2 months. If the neovascularization is again quiescent, I will extend to 3 months, and that way I am at quarterly doses within the first three to four injections. In an ideal setting, these patients are then maintained at quarterly dosing, but if there is a concern for this frequency of visits or a concern for noncompliance, I will consider the use of PRP.

Dr. Chiang: Getting the patient to buy into the follow-up protocol is really important and not just for the purposes of administering the anti-VEGF therapy. We need to get patients back in the office so we can monitor them. One of the prevailing thoughts around using laser in this setting is that it provides security in the event that a patient starts missing appointments. Although laser provides some durability, it is still possible to see progression, especially if the laser treatment is incomplete, so compliance is still important even with laser. In some cases, I have seen laser drive patients away either due to pain or because they think they are stabilized for good.

Dr. Wykoff: Let us consider treatment burden between the arms in Protocol S; specifically, the laser arm had a substantially lower treatment burden through 5 years.

- In the PRP arm, 49% of patients required one laser session, just 11% needed additional PRP for the treatment of PDR in years 3, 4, and 5 cumulatively, and the median number of visits through 5 years was 21; although, it is important to recognize that 58% of the PRP arm also received anti-VEGF dosing for DME with an average of 5.4 anti-VEGF injections given through 5-years.

- In comparison, in the anti-VEGF arm, there were an average of 19.2 injections given through 5-years, between 27% and 37% of eyes required no injections in years 3, 4, and 5, and the median number of visits through 5-years was 43.

Dr. Chiang: I agree. Keep in mind, 50% in each group had vitreous hemorrhage at the 5-year time point in Protocol S. To me this suggests the possibility that both groups were being undertreated over time.

Dr. Baumal: Both of those points are a reason why in real life clinical management, many retinal physicians eventually treat PDR with a combination of laser and anti-VEGF injections.

Dr. Wykoff: Let us consider visual field outcomes in Protocol S.

- In the first 2 years, there was a difference between the arms, with preservation of visual field in the anti-VEGF arm compared to visual field loss in the PRP arm.

- At 5 years, there remained a statistically significant difference favoring the anti-VEGF arm; but both arms experienced decline in visual field.

What was driving this decline in visual field in years 3, 4, and 5? Is it disease progression or were the injections causing visual field loss?

Dr. Kiss: I believe these patients were undertreated, even in the anti-VEGF group. The rate of vitreous hemorrhage supports that assumption. There is a perception that with a disease like age-related macular degeneration, the patient is going to be on anti-VEGF therapy forever, whereas in DR, there is an endpoint to therapy. I am not sure I believe that. Even though anti-VEGF therapy is reversing the disease in DR, time is going to catch up with those patients. Although we are helping patients by reducing the treatment burden with anti-VEGF injections in the short term, over the long term, we might actually be doing them a disservice by increasing the intervals between injections.

Dr. Wykoff: The visual field may have not have deteriorated in the anti-VEGF arm in years 3, 4, and 5 if those patients had been treated more aggressively.The other hypotheses are that the injections damage the nerve fiber layer, perhaps secondary to fluctuations in pressure, or blocking VEGF causes damage to the ganglion cells, perhaps through removal of a neuroprotective effect.

Dr. Kiss: That is plausible, although I am not sure we are going to have an answer to that until we see a trial performed with sustained delivery of anti-VEGF drugs in DR or DME. The fact remains, though, there is a difference in the visual field data.

Dr. Wykoff: Let us consider VA.

- The difference between the arms at 2 years was lost by year 5.

- With 2-year data, we could tell patients that anti-VEGF injections led to better visual field and VA outcomes with fewer vitreous hemorrhages, but by the end of year 5, the functional differences between the arms are less distinct.

Dr. Chiang: I wonder if that is because only 66% of patients completed follow-up to 5 years. What happened to the eyes of patients who did not complete the study?

Dr. Wykoff: The individuals who did not complete the study tended to have higher HbA1c levels, worse baseline VA, and more advanced DR at baseline. One can make the case that losing the sickest eyes in the study may be why the VA outcomes are so good in both arms.

Dr. Chiang: What is interesting to me is that this is in the setting of a controlled clinical trial, and yet about a third of patients were lost to follow-up. The level of noncompletion surprised me, and I think it underscores how complex this condition is and how many factors are involved with treatment.

Dr. Wykoff: Once a patient has declared himself or herself noncompliant, do you then use PRP?

Dr. Kiss: I do not use laser because I have not seen any evidence where PRP or other forms of laser outperform anti-VEGF therapy especially in the setting of patients who do not adhere to follow-up.

Dr. Coney: This is based on my own personal experience, but my sense is that I am able to salvage an eye that had previous laser, whereas those that never received laser previously tend to develop worse disease. This phenomenon may be partly attributable to the effects of anti-VEGF agents, which forestall development of severe complications, but actually somewhat facilitate the potential to develop microangiopathy in later, advancing stages of the disease.

PANORAMA

Dr. Wykoff: The PANORAMA study randomized patients with moderately severe to severe NPDR with no DME to sham versus two different aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) treatment regimens.15 Through 24 weeks, 58.4% of those treated with aflibercept had at least two-step improvement in DR compared to 6% in the sham arm. Another important piece of data is that 25.6% of the sham arm progressed to proliferative disease or center-involved DME versus 4.5% of the aflibercept population. Does this data change the way you practice?

Dr. Chiang: The data confirm that DR is progressive and suggest that we should be thinking about treating earlier with anti-VEGF injections, which means we should be pushing for earlier detection of DR. Especially for the patient who has already suffered severe vision loss from DR in one eye, they could benefit from earlier initiation of treatment.

Dr. Kiss: The data are compelling, but there is another question that is still unanswered: what were the outcomes in the patients in the sham arm who developed center-involving ME? There may be an opportunity at that time to treat versus starting earlier. And so, the data make me consider treating NPDR, but I am not ready to start that just yet.

Dr. Coney: My question is how much DME are you okay to watch? I do not think we have clear guidance on eyes with mild ME with good VA. That ultimately says to me that we need to determine the treatment endpoints for each patient, and those endpoints may vary. Some patients are happy to get to 20/20, while others want to keep going until the edema is gone.

Dr. Baumal: There may be a rationale to offer anti-VEGF treatment to select patients with very severe NPDR with the goal of yielding regression of DR severity. It may be useful to focus on newer imaging or systemic biomarkers of DR progression to identify eyes at highest risk of progression to PDR to consider for earlier therapy.

Dr. Kiss: In the major studies that we have to date, including RISE/RIDE, Protocol S, and PANORAMA, there is no indication that delayed treatment for DR has an impact on VA outcomes.

Dr. Coney: If treatment is not going to be offered to the patient with mild edema, I think there is need for very close monitoring. We do not have established literature on the subject, but there is at least an emerging understanding that peripheral ischemia is a negative prognostic sign in an eye with DME.