Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) can complicate rhegmatogenous retinal detachments (RDs) and contribute to poor visual outcomes.1 PVR is an irregular scarring process characterized by the growth of membranes on both surfaces of a detached retina and sometimes on the vitreous.2,3 PVR evolves from abnormal retinal cell proliferation to form membranous sheets and ultimately tractional sheets and bands that can contribute to recurrent RD.4

PVR is most commonly graded according to the updated Retina Society classification as follows:5 Grade A indicates the earliest process with pigment clumping in the vitreous; Grade B indicates rolled edges of retinal tears; Grade C indicates the formation of preretinal or subretinal bands.6-8

Management of subretinal bands can be complex, and currently there is no consensus on its management.6,9,10 In many cases, surgical peeling is not necessary, as it may not change postoperative outcomes; observation may be appropriate in select cases.9,11 In instances where subretinal bands create persistent traction that prevents retinal reattachment, surgical removal may be required to achieve the best reattachment rates and visual outcomes.10

Machemer first described removal of subretinal bands via a subretinal approach.12 In two of the three cases, he reported the patient’s BCVA had improved, and the RD did not recur following surgery.12 Later, the same author introduced access retinotomies to aid in removing subretinal strands of PVR.13 Since then, several reports have highlighted the efficacy of access retinotomy when combined with an effective treatment of the retinal break(s) by photocoagulation or cryotherapy.9,14-17

In our opinion, the best approach to manage subretinal PVR bands begins with assessment of the amount of traction and the status of the vitreous. If the traction induced by the subretinal band(s) is mild or the patient is young without a posterior vitreous detachment, often the most reasonable approach may be to repair the RD but observe the subretinal band(s). If the traction is more significant or if the band is more posterior, then removing the band should be considered at the time of RD repair. Subretinal bands can be removed via access retinotomies, a larger retinectomy to allow peeling of larger sheets that are not amenable via small retinotomy, or a retinectomy that excises the subretinal bands with the adjacent retina. The following cases highlight various approaches.

Case 1: RD Repair and Observation

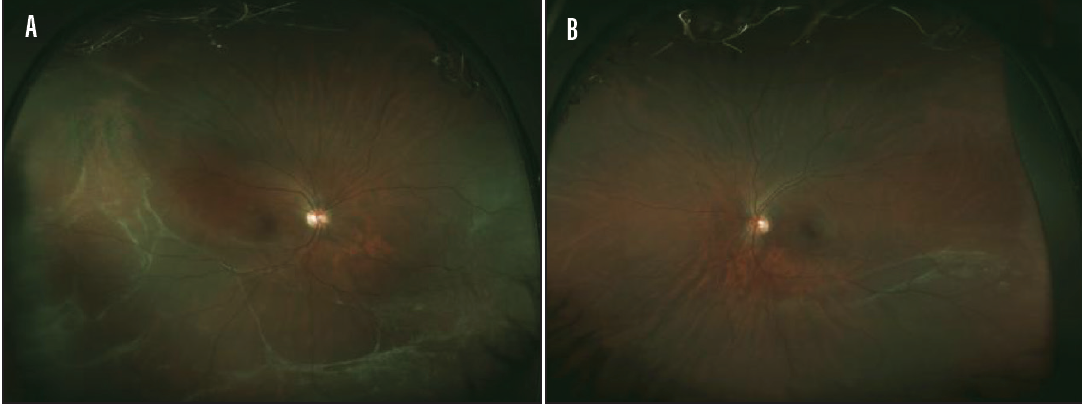

This 25-year-old female with a history of high myopia presented with blurry vision superiorly in the right eye. Her VA was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. On clinical examination, we found the patient had bilateral chronic inferior rhegmatogenous RDs with atrophic holes and subretinal bands exerting mild traction on the retina (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Widefield fundus photo of the right eye (A) showing chronic inferior rhegmatogenous RD with atrophic holes and minor subretinal band. The left eye (B) is similarly showing inferior rhegmatogenous RD with a minor subretinal band.

The RD was repaired with a staged bilateral scleral buckle placement combined with external cryotherapy and drainage of subretinal fluid. Because the subretinal bands were peripheral and exerting minimal to no traction, we decided to observe them.

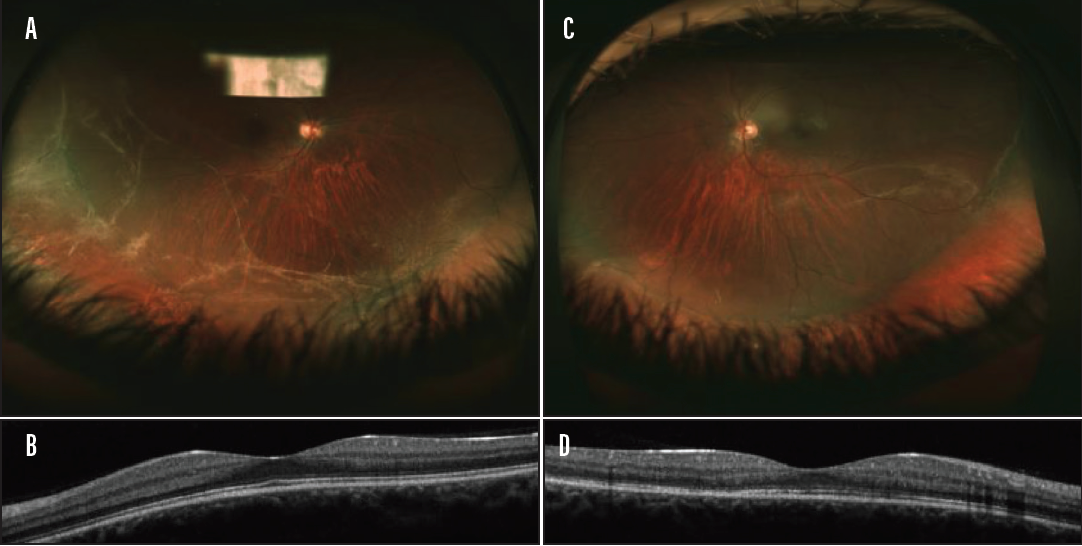

One month postoperatively, both eyes exhibited attached retinas (Figure 2), and VA was 20/25 in both eyes. At the patient’s most recent visit, 2 years postoperatively, the retinas of both eyes were still attached, and the patient’s VA was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye.

Figure 2. Widefield fundus photo (A) and OCT (B) of the right eye 1 month postoperative. OCT shows attached retina without traction. Widefield fundus photo (C) and OCT (D) of the left eye 1 month postoperatively. OCT shows no traction on the retina.

In this case, observation of the subretinal bands was appropriate, as they were not inducing significant traction on the retina.

Case 2: Access Retinotomy and Subretinal Band Removal

This 40-year-old male had a history of RD in the right eye treated with a pars plana vitrectomy with silicone oil 4 years prior. He had slowly lost vision over the last year, and his VA on presentation was hand motion.

On clinical examination, we determined the patient had rhegmatogenous RD with extensive chorioretinal scarring and fibrosis including the macula, as well as subretinal bands inducing traction on the macula.

The patient underwent a 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with iris hooks, silicone oil removal, and peeling of the preretinal membranes. At this point in the surgery, a large subretinal band was noted tenting under the detached retina. An access retinotomy was created with intravitreal diathermy, and the band was removed using Grieshaber Maxgrip forceps (Alcon). The retina had improved mobility after removal of the band, and retinal reattachment was completed with perfluorocarbon liquid and endolaser followed by fluid-air exchange and silicone oil tamponade (Video).

In this video, John B. Miller, MD, describes how he creates an access retinopathy adjacent to the subretinal band in an effort to remove the band with forceps.

Discussion: Access Retinotomy

While there are several different approaches to creating an access retinotomy, we suggest making it adjacent to, rather than directly above, the subretinal band when possible. Placement of the retinotomy directly over the subretinal band can inadvertently sever the band, leading to retraction and an inability to access the band.

In removing the band, the surgeon should anticipate the angle at which the forceps will pass through the access retinotomy to grasp the band.

The band should be removed slowly with careful attention to the retinotomy. Rapid pulling or the presence of large bands can lead to unintended expansion of the retinotomy. The direction of the pulling force should be aligned with the linear axis of the band. If the band is particularly long or the space between the retinotomy and the scleral wall is inadequate, the surgeon can use the light probe as a pulley to change the pulling angle or increase the effective distance traveled by the forceps. If the band is extensive, hand-over-hand with two forceps is also a reasonable option with illumination by a chandelier.

Conclusion

These cases highlight different approaches to managing subretinal bands. PVR and subretinal bands are associated with higher failure rates of RD repair and recurrent RDs. Surgeons must weigh the possible need for removal versus observation of subretinal bands to ensure reattachment, which can be a complex and challenging task. Once the decision has been made to remove a band, several options, such as access retinotomy, retinectomy with broad peeling, or excisional retinectomy, are available. Appropriate decision-making and careful technique can ensure surgical success.

1. The classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:121-125.

2. Pastor JC, Fernández I, Rodriguez de la Rua E, et al. Surgical outcomes for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in phakic and pseudophakic patients: the Retina 1 Project—report 2. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:378-382.

3. Ciprian D. The pathogeny of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2015;59:88-92.

4. Amarnani D, Machuca-Parra AI, Wong LL, et al. Effect of methotrexate on an in vitro patient-derived model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:3940-3949.

5. Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Freeman HM, et al. An updated classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:159-165.

6. Sternberg P Jr, Machemer R. Subretinal proliferation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:456-462.

7. Trese MT, Chandler DB, Machemer R. Subretinal strands: ultrastructural features. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223:35-40.

8. Wallyn RH, Hilton GF. Subretinal fibrosis in retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:2128-2129.

9. Michels RG. Surgery of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 1984:4:63-83.

10. Lewis H, Aaberg TM, Abrams GW, et al. Subretinal membranes in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1403-1414; discussion 1414-1415.

11. Scott IU, Flynn HW, Murray TG, Feuer WJ; Perfluoron study group. Outcomes of surgery for retinal detachment associated with proliferative vitreoretinopathy using perfluoro-n-octane: a multicenter study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:454-463.

12. Machemer R. Surgical approaches to subretinal strands. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:81-85.

13. Machemer R. Retinotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92:768-774.

14. Khan MA, Brady CJ, Kaiser RS. Clinical management of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina. 2015;35:165-175.

15. Reinking U, Lucke K, Bopp S, Laqua H. [Results after retinotomy and retinectomy in the treatment of complicated retinal detachment]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1990;197:382-385.

16. Blumenkranz MS, Azen SP, Aaberg T, et al. Relaxing retinotomy with silicone oil or long-acting gas in eyes with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Silicone Study Report 5. The Silicone Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:557-564.

17. Shalaby KA. Relaxing retinotomies and retinectomies in the management of retinal detachment with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:1107-1114.